Ruth Kluger's Holocaust memoir

Today I read this, on the question of the existence of altruism, in Ruth Kluger's Holocaust memoir,

Landscapes of Memory:

Selection, there was to be a selection. At a certain barracks at a certain time, women between the ages of fifteen and forty-five were to be chosen for a transport to a labor camp. Some argued that up to now every move had been for the worse, that one should therefore avoid the selection, stay away, try to remain here. My mother believed - and the world has since agreed with her - that Birkenau was the pits, and to get out was better than to stay. But the word Selection was not a good word in Auschwitz, because it usually meant the gas chambers. One couldn't be sure that there really was a labor camp at the end of the process, though it seemed a reasonable assumption, given the parameters of the age group they were taking. But then, Auschwitz was not run on reasonable principles.

My mother had reacted correctly to the extermination camp from the outset, that is, with the sure instinct of the paranoid. Her suicide proposal of the first night is evidence of her understanding. And when I wouldn't go along with her then, she managed to take the first and the only way out. Time has proved that she was right all along, and yet I still think it was not her reasonableness but an old and deep-seated sense of being persecuted which enabled her to save our lives. Psychologists like Bruno Bettelheim have tried to persuade us that a sane person who hasn't been spoiled by a disabling bourgeois education should be able to adjust to new conditions, even if they are as outlandish as those of a concentration camp. The saner, the better the chance of survival is the bottom line of this type of argument. I think the opposite is true. I think that people suffering from compulsive disorders, such as paranoia, had a better chance to pick their way out of mass destruction, because in Auschwitz they were finally in a place where the social order (or social chaos) had caught up with their delusions. If you think that your mind is the most precious thing you own, you are right, because what have we got that defines us other than reason and love? But in Auschwitz love couldn't save you, and neither could reason. Madness, perhaps. There are no absolute means of salvation, and there are times when even paranoia may work. It wasn't the last time that my mother thought she was pursued, and maybe it wasn't the first time. But it took the Shoah to prove her right for once.

But isn't the price she paid too high: this madness that she carried inside her, like a sleeping tomcat? The cat would occasionally stretch, yawn, arch his back, softly case the joint, suddenly chatter with his teeth, reach with sharp claws for a bird, and go to sleep again - leaving the bloody feathers for me to clean up. I don't want to carry such a predator inside of me, even if he could save my life in the next extermination camp.

Two SS men conducted the selection, both with their backs to the rear wall. They stood on opposite sides of the so-called chimney, which divided the room. In front of each was a line of naked, or almost naked, women, waiting to be judged. The selector in whose line I stood had a round, wicked mask of a face and was so tall that I had to crane my neck to look up at him. I told him my age, and he turned me down with a shake of his head, simply, like that. Next to him, the woman clerk, a prisoner, too, was not to write down my number. He condemned me as if I had stolen my life and had no right to keep it, as if my life were a book that an adult was taking from me, just as my uncle had taken the Bible from me because I was too young to read it. Later I saw the selector's image in Kafka's door keeper, who won't grant a man entrance to his own space and light.

My mother had been chosen. No wonder: she was the right age, a grown-up woman. Her number had been written down, and she would leave the camp shortly. We stood on the street between the two rows of barracks and argued. She tried to persuade me that I should try a second time, with the other SS man in the other line, and claim that I was fifteen.

The month of June 1944 was very hot in Poland, and therefore both the front and the rear doors of the barracks stood open. The back entrance was guarded, but the detail consisted of inmates, and my mother felt I could sneak by and take another turn. And this time, please don't be a fool and tell them your real age of twelve. I got angry and was half desperate. `I don't look older,' I remonstrated. I felt she half wanted me to step in a pile of shit, like the time a few years earlier when she had urged me to go to the movies despite the legal prohibition. (I repeat: my mother and I were very unfair to each other.) The difference between twelve and fifteen is enormous for a twelve-year-old. I was to add a quarter of my entire life. In Theresienstadt, in L4r4, they had put the different age groups into different rooms. A mere difference of one year had meant another room, another community. The lie which my mother proposed was so transparent: three years! Where was I to find them?

I was anguished and frightened, but this was not the profound fear that overwhelmed me when I looked at the chimneys, the crematoria, spitting flames at night and smoke by day. When that fear gripped me, it was like the psychological equivalent of epileptic fits. The fear I felt now was more like the bearable fear of malicious grown-ups, a fear with which I could cope. For what would become of me if I had to stay in Birkenau without my mother? Well, that was out of the question, she assured me. If I wouldn't try the selection a second time, she would stay, too. She'd like to see who could separate her from her child. Only it wasn't a good idea, and would I please listen to what she was telling me, she said, without paying attention to my conclusive counterarguments. `You are a coward,' she said half desperately, half contemptuously, and added, `I wasn't ever a coward.' So what could I do but go in a second time, but with the proviso that I would try thirteen, never fifteen. Fifteen was preposterous. And if I get into trouble, it's your fault.

The space between the barracks I was to invade in order to reach the back door was guarded by a cordon of men. My mother and I watched them carefully for a minute or so. `Now!' we realized, and I sneaked by as the two men in charge happened to call out to each other. I bent over a little to appear smaller, or to make use of the shadow of the wall, turned the corner, and entered through the door, unobserved.

The room was still full of women. A kind of orderly chaos reigned which I associate with Auschwitz. The much-touted Prussian perfection of camp administration is a German myth. Behind every good organization is the presumption that there is something worth keeping and organizing. Here the organization was superficial, because there was nothing valuable to organize or retain. We were worthless by definition. We had been brought here to be disposed of, and hence the waste of Menschenmaterial, human substance, as the inhuman German term has it, was immaterial, to use another inhuman term. Basically the Nazis didn't care what went on in the Jew camps, as long as they were no bother. The selecting SS officers and their helpers stood with their backs to me. I went unobtrusively to the front door, took off my clothes once more, and quietly went to the end of the line. I breathed a sigh of relief to have managed so far so well, and was happy to have been smarter than the rules. I had proved to my mother that I wasn't chicken. But I was the smallest, and obviously the youngest, female around, undeveloped, undernourished, and nowhere near puberty.

I have read a lot about the selections since that time, and all reports insist that the first decision was always the final one, that no prisoner who had been sent to one side, and thus condemned to death, ever made it to the other side. All right, I am the proverbial exception.

What happened next is loosely suspended from memory, as the world before Copernicus dangled on a thin chain from Heaven. It was an act of the kind that is always unique, no matter how often it occurs: an incomprehensible act of grace, or put more modestly, a good deed. Yet the first term, an act of grace, is perhaps closer to the truth, although the agent was human and the term is religious. For it came out of the blue sky and was as undeserved as if its originator had been up in the clouds. I was saved by a young woman who was in as helpless a situation as the rest of us, and who nonetheless wanted nothing other than to help me. The more I think about the following scene, the more astonished I am about its essence, about someone making a free decision to save another person, in a place which promoted the instinct of self-preservation to the point of crime and beyond. It was both unrivaled and exemplary. Neither psychology nor biology explains it. Only free will does. Simone Well was suspicious of practically all literature, because literature tends to make good actions boring and evil ones interesting, thus reversing the truth, she argued. Perhaps women know more about what is good than men do, since men tend to trivialize it. In any case, Well was right, as I learned that day in Birkenau: the good is incomparable and inexplicable as well, because it doesn't have a proper cause outside itself, and because it doesn't reach for anything beyond itself.

I can't keep SS men apart - to me they are all the same uniformed wire puppet with polished boots. Even when Eichmann was tried and executed, I was embarrassingly indifferent to the whole process. These people were one single phenomenon, as far as I was concerned, and their different personalities were irrelevant. Hannah Arendt offered the counterpart to Simone Well's reflections on goodness when she pointed to the simple fact that evil is committed in the spirit of mental dullness and narrow-minded conformity - what she called banality. Her reflections on evil caused much indignation among men, who understood, though perhaps not consciously, that this deromanticization of arbitrary violence was a challenge to the patriarchy. Perhaps women know more about evil than men, who like to demonize it.

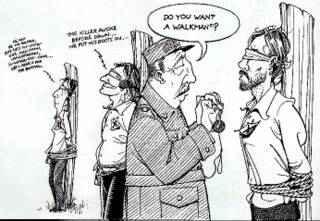

The line moved towards an SS man who, unlike the first one, was in a good mood. Judging from photos, he may have been the infamous Dr. Mengele, but as I said, it doesn't matter. His clerk was perhaps nineteen or twenty. When she saw me, she left her post, and almost within the hearing of her boss, she asked me quickly and quietly and with an unforgettable smile of her irregular teeth: `How old are you?' `Thirteen,' I said, as planned. Fixing me intently, she whispered, `Tell him you are fifteen.'

Two minutes later it was my turn, and I cast a sidelong look at the other line, afraid that the other SS man might look up and recognize me as someone whom he had already rejected. He didn't. (Very likely he couldn't tell us apart any more than I had reason to distinguish among the specimens of his kind.) When asked for my age I gave the decisive answer, which I had scorned when my mother suggested it but accepted from the stranger. `I am fifteen.'

`She seems small,' the master over life and death remarked. He sounded almost friendly, as if he was evaluating cows and calves.

`But she is strong,' the woman said, `look at the muscles in her legs. She can work.'

She didn't know me, so why did she do it? He agreed - why not? She made a note of my number, and I had won an extension on life.

Every survivor has his or her `lucky accident' - the turning point to which we owe our lives. Mine is peculiar because of the intervention of the stranger. Virtually all those still alive today who have the Auschwitz number on their left arm are older than I am, at least by those three years that I added to my age. There are exceptions, like the underage twins on whom Dr. Mengele performed his pseudomedical experiments. Then there are some who were my age, but who were selected at the ramp to be sent immediately on to the labor camps, and who were thought to be older because they wore several layers of clothing, by way of transporting a wardrobe. They were not tattooed because they weren't in the camp. To get out of the camp, you really had to have been alive longer than twelve years.

I have always told this story in wonder, and people wonder at my wonder. They say, okay, some persons are altruistic. We understand that; it doesn't surprise us. The girl who helped you was one of those who likes to help. A young American rabbi says that after my buildup he expected a more heroic tale. Maybe he has seen too many action films or read too many Bible stories, the kind that tout male virtues, muscle over mind, noise over quiet resolve. But don't just look at the scene. Focus on it, zero in on it, and consider what happened. There were two of them: the man who had power he could exert on a random object, for better or for worse. He probably didn't believe that the labor of a starved little girl would promote the German war effort considerably or retard the final solution to a noticeable extent. He had to decide the case one way or the other, list or not list my number. Just then it suited him to listen to his clerk. And she is the other. I think his action was arbitrary, hers voluntary. It must have been freely chosen, because anyone knowing the circumstances would have predicted the opposite, or at least shoulder-shrugging indifference. Her decision broke the chain of knowable causes. She was an inmate, and she risked a lot when she prompted me to lie and then openly championed a girl who was too young and small for forced labor and completely unknown to her. She saw me stand in line, a kid sentenced to death, she approached me, she defended me, and she got me through. What more do you need for an example of perfect goodness? Never and nowhere was there such an opportunity for a free, spontaneous action as in that place at that time. It was moral freedom at its purest. I saw it, I experienced it, I benefited from it, and I repeat it, because there is nothing to add. Listen to me, don't take it apart, absorb it as I am telling it and remember it.

But perhaps you are of the opposite camp and claim that there is no such thing as altruism, that every action is motivated by some kind of selfishness, even if such egotism is no more than the consciousness of free choice. In that case, of course, freedom itself is a mere illusion as well. And perhaps you are right, and there is no absolute in these matters, but only approaches to goodness and to freedom. The main characteristic of freedom is its unpredictability. And no one has been able to predict human behavior with the same accuracy as, for example, the behavior of amoebas. Dogs, horses, and cows are semipredictable, but with humans there is never more than a certain degree of probability. People can change their minds at the last moment, and even if we knew everything about a person and stored it in the most advanced computer system, we could still not foresee the mental movement of a woman whom I didn't know, whom I never saw again, deciding to save me and succeeding.

And therefore I think it makes sense that the closest approach to freedom takes place in the most desolate imprisonment under the threat of violent death, where the chance to make decisions has been reduced to almost zero. (And where is the zero point? The gas chambers are zero, I believe, when the men in their final contortions are forced by a biological urge to step on the children. But how can I be sure?) In a rat hole, where charity is the least likely virtue, where humans bare their teeth, and where all signs point in the direction of self-preservation, and there is yet a tiny gap - that is where freedom may appear like the uninvited angel. If a prisoner passed on the beatings he received to those even more helpless than he, he was merely reacting as psychology and biology would expect him to. But if he did the reverse? And so one might argue that in the perverse environment of Auschwitz absolute goodness was a possibility, like a leap of faith, beyond the humdrum chain of cause and effect. I don't know how often it was consummated. Surely not often. Surely not only in my case. But it existed. I am a witness".